This article originally appeared in The Peak. I originally wanted to do this big meshed narrative about the cyclic nature of how these scenes rise and fall, but I ended up just doing a mash-up interview and review of the two films. I’m not sure I did them justice, so let me reiterate: these are two as important films on the local culture of Vancouver as you will ever find, and you should seek them out.

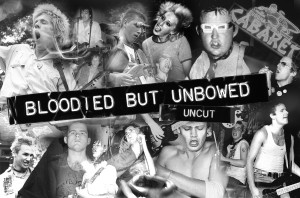

Two punk documentaries premiered at the DOXA Documentary Festival this year. One speaks to the rise of the Vancouver punk machine, the other documents the remains of a scene with nowhere to call their own. Together, they paint a portrait of alternative music in Vancouver past and present, its enslavement to the government, and the seeming desire to see it stamped out altogether. Despite this, their existence signals the continuing resilience of the culture and are both fascinating looks at our shared history and future.

He’s 20 if he’s a day. An impossibly young looking Joe Shithead smokes a cigarette in Stanley Park, readying himself for the Anti-Canada Day show at Prospect Point. He’s speaking almost over the journalist’s microphone, regarding it like so many mosquitoes. He’s talking about the state of music in Vancouver at the start of Susanne Tabata’s punk documentary Bloodied But Unbowed, dismayed that it has become mostly about “Fleetwood Mac and disco.”

“We can’t play because we’re punks. Because this isn’t a free country,” he says. They’re waiting to see if the show will even happen, their permits having been denied, and are lobbying a Christian picnic group to lend them theirs. It’s a bizarre introduction to a document of an equally bizarre time for Lower Mainland music, a scene born in a regional backwater of an international backwater and fueled by politics, youth, and noise.

Tabata herself is tired. After the world premiere screening of Bloodied But Unbowed to a capacity crowd (and a long after-party) that was beset by technical issues, you can hear the fatigue in her voice. A veteran of CiTR and the alternative and no-holds barred Nite Dreems program, Tabata was wading in the thick of the Vancouver punk scene in its heyday. Her newest film pays homage to a place and time that was “honest and raw,†or as Tabata puts it, a time of “spontaneous creativity and camaraderie without bitter rivalry.”

Mary Jo Kopechne of The Modernettes stayed the night after reuniting with friends long gone. “It was overwhelming. I’m still taking it all in,” she says. The emotions brought by the film aside, Kopechne was one among an attendee list packed with many of the same stars interviewed in the film. Filled with long hair and leather jackets, the theatre was a coming together of the faithful and the participants of an era past.

Bloodied But Unbowed’s list of interviewees is an encyclopedic look at who was who in the late 1970s and early 1980s: Zippy Pinhead and D.O.A., Gerry Hannah and The Subhumans, Jade Blade and The Dishrags, Colin Griffiths and The Pointed Sticks, and Art Bergmann of Young Canadians feature prominently in a film that could have stood on the quality of these interviews alone. Instead, Tabata weaves them into a cohesive historical tome of this period of art and culture. It packs a staggering amount of information, music, and sentiment into its 74-minute run time, surveying the vast landscape of art, politics, and social structure that bygone punks created.

Narrated by Billy Hopeless and strung together under different topic headings, Bloodied charts the rise of forerunners D.O.A. and The Subhumans, from their shared elementary school origins to the creation of a friendly rivalry in the community. Their differing styles would lay the groundwork for a scene that was obsessed with “versus,” resentful of their outcast status and yearning for a community. The film delves into the unlikely alliance they had with the gay community (“when the punks were around, it would take the heat off us”), its association with yippie politics (“using the weapons of the enemy against them”), and the confused relationship the scene had with women. Kopechne embodied this conflict, getting ragged on for playing with persons of both genders. It raises many criticisms to go along with its praise of the community, and finds a balance in its moment of levity and moments of intense heartache. Interviews with Art Bergmann are particularly intense, the scene portrayed as a sun he flew a touch too close to.

Bloodied displays the natural trajectory of a narrative film, which is fitting for the scene it documents. Punk has been declared dead almost from the moment it began, and the documentary is specific in its fingering of heroin as one of the culprits in the death of Vancouver punk: in part, it acts as a eulogy to those that could not be added to the list of participants by virtue of their passing.

“It died a natural death,†admits Tabata, noting that scenes rise and fall with the passing of youth and the “packaging and selling back” of its auspices. “It’s a very dramatic end to a documentary, a very dramatic finish. People started becoming more aware of themselves.†Some say, “The ‘80s happened.†Some say the violence got excessive. Whatever it is, the mohawks and patches sported by today’s youth are empty reminders that the dregs still look for a place to call home. In a way, being unable to fashion something new seems more painful. The only thing worse would to be beaten, bloodied, and have no place to go to lick your wounds. Not like something like that would ever happen.

Vancouver punk died, but it didn’t die all the way. There was still some life in the bones of the scene, that energy and momentum shifting into the emerging hardcore and post-punk, metal and noise scenes that jockeyed for position in the aftermath of Smilin’ Bhudda punk rockers. Like all movements, this music and art needed a home, and up until recently found one in the form of the Cobalt Motor Hotel. No Fun City is in part a chronicle of the closing of that venue, and an exploration of what makes Vancouver “no fun,” with co-directors Kate Kroll and Melissa James putting their cameras right in the middle

Spoiler alert: the Cobalt as it was is no more. Despite the efforts of the community and proprietor Wendy 13, the Cobalt as it is now is a completely different animal. The documentary shows an obstinate Wendy 13 saying that everyone who wants her shut down “won’t win.” But they did. Kroll and James admit this fact. “I think they won this round. It’s a strong community. So, regardless, things kept on going,” says Kroll and James.

The emotional climax of the film comes with the closing of the venue, the final night a must attend event for any and all associated with the scene. The booze, tears, and breakables fly freely. Though questions to her efficacy in dealing with the city and the Cobalt landlords are often raised, No Fun City captures a very genial Wendy 13, and you can’t help but feel for her in the end. “She will rise again,” says James. “No one would go into that place. She took that and with her dedication and passion made it into a place people wanted to go.” Despite that, a chain of complaints, coming down from residents in the area through the city to her landlords resulted in the closing of the Cobalt.

No Fun City examines the efforts of other noted venue promoters, such as Malice Liveit and David Duprey. The former a long-time concert organizer and manager of the now defunct Sweatshop and the latter a prominent Vancouver area developer have differing views and tastes about how the business of the scene is conducted, but both agree that without a home, Vancouver music scenes are doomed to die. Duprey is a proponent of gentrification, but seems to preach a gospel of responsible development, one that doesn’t kill art and music, ultimately driving away the young to other cities. While Malice and Duprey ultimately could not find common ground in their venture at the Rickshaw Theatre, they both agree that city policy regarding “dancing permits” and million-dollar liquor licences they are reluctant to grant are bureaucratic insanity. The result is an influx of illegal venues and shows, the counter-point of which is Duprey operating the Rickshaw to this day on temporary liquor licences.

The juxtaposition of the scene versus condo dwelling enemies is one that runs through the film, pointing a finger at the “not in my backyard” attitude that is tossing the scene out into the street. It initially comes across as a conflict between the haves and the have-nots, but James is loathe to draw such a definite line. “I know some pretty well off people that listen to punk and metal. In general, yes, but mainly the cost of living in Vancouver is huge. There’s no space. The city wants to encourage urban living, and in so doing are killing the urban vibe.”

No Fun City is an excellent look at some of the reasons why the city is now trying to change policies to fight the moniker, but even more it is a look at a people and a scene looking for some kind of headbangers’ Israel. They seem like a group that might be at their most natural underfoot, and No Fun City is a rallying call those in a scene looking to be reborn in blood, beer, and sweat.

Comments Off on Sunrise, Fucking Sunset: The Rise and Endless Fall of Vancouver Punk